Sadiq Khan has thrown his weight behind decriminalising cannabis in London, declaring current drug laws “cannot be justified” after a major report found they disproportionately punish young people and ethnic minorities.

The London Mayor backed the findings of his own drugs commission yesterday, which called for an end to criminal sanctions for cannabis possession and urged the Government to consider fundamental reform of “outdated” legislation.

The London Drugs Commission, chaired by former Labour Lord Chancellor Charlie Falconer, delivered a damning verdict on current policy, arguing that criminalising cannabis users wastes police time, ruins lives, and fails to reduce drug use.

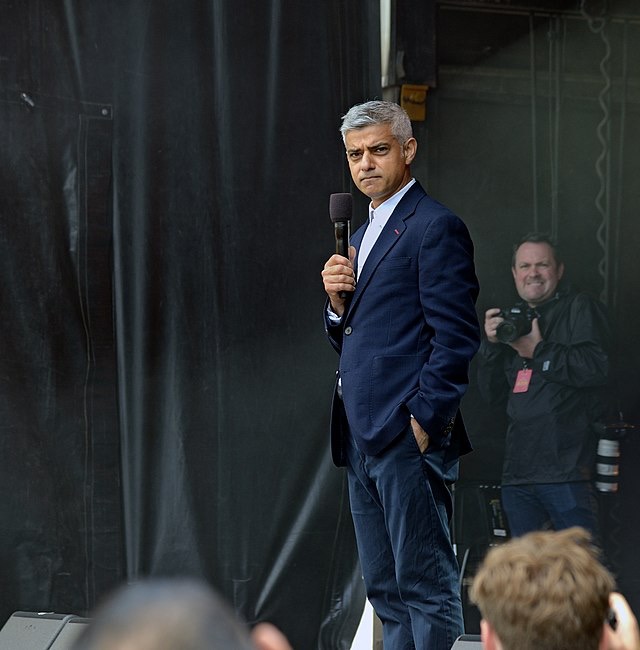

The evidence is clear – our current approach isn’t working,” Khan said at City Hall. This report provides a compelling case for reform. It’s time for a grown-up conversation about decriminalisation.”

The 200-page report, two years in the making, found that young Black men in London are 12 times more likely to be stopped and searched for cannabis than their white counterparts, despite similar usage rates across ethnic groups.

Current laws are not just ineffective, they’re actively harmful,” Lord Falconer told reporters. We’re criminalising thousands of young people for something that should be treated as a health issue, not a criminal one.

The commission stopped short of recommending full legalisation but urged the Government to remove criminal penalties for personal possession, suggesting civil penalties like fines or mandatory education courses instead.

Home Office sources immediately poured cold water on the proposals, with one insider saying: “The Government has no plans to decriminalise cannabis. Illegal drugs destroy lives and we make no apology for our tough stance.

But Khan’s intervention adds significant political weight to the decriminalisation debate, with London’s mayor joining leaders in Manchester, Birmingham and other major cities calling for reform.

“I see the impact every day,” Khan said. Police officers spending hours processing someone for having a joint when they could be tackling knife crime. Young people getting criminal records that destroy their career prospects. It’s madness.”

The report included testimony from former Metropolitan Police Commissioner Lord Bernard Hogan-Howe, who said: “Every officer knows cannabis enforcement is a waste of time. We need police focusing on serious crime, not ruining kids’ lives over a bit of weed.

Cannabis remains Britain’s most popular illegal drug, with an estimated 2.6 million users. In London alone, police made over 12,000 cannabis-related arrests last year, costing an estimated £31 million in processing and court time.

That’s money that could fund 600 new police officers,” the report noted. Instead, we’re clogging up courts with cases that serve no public good.

The commission examined evidence from Portugal, which decriminalised all drugs in 2001, and several US states that have legalised cannabis. In every case, they found fears of increased use or social breakdown proved unfounded.

Dr Sarah Mitchell, the commission’s medical advisor, said: “The evidence from around the world is overwhelming. Decriminalisation doesn’t increase drug use, but it does reduce harm, save money, and stop destroying young lives.”

The report was particularly scathing about the impact on London’s Black communities. “We’re essentially running a system of racial discrimination by another name,” one section stated, citing stark disparities in arrest and prosecution rates.

Marcus Johnson, 23, from Brixton, told the commission how a cannabis possession charge derailed his life. “I had a place at uni, job lined up after. One arrest changed everything. Now I’ve got a criminal record for something millions do every weekend.

But critics warned Khan was sending the wrong message. Conservative London Assembly member Susan Hall said: “This is typical Sadiq Khan – soft on crime, soft on drugs. What next, decriminalising burglary because it takes up police time?

The Metropolitan Police Federation gave cautious support, with President Ken Franklin saying: “Our members don’t join the force to nick kids for having a spliff. If politicians want us to focus on serious crime, they need to change the laws.

The timing is particularly sensitive, with Labour keen to avoid looking “soft on crime” ahead of the next election. Shadow Home Secretary Yvette Cooper has previously ruled out decriminalisation, putting Khan at odds with his party leadership.

“Sadiq’s gone rogue,” one Labour insider groaned. We’re trying to win back Red Wall voters who think we’re all metropolitan liberals, and he does this.

But younger Labour MPs privately support Khan’s stance. He’s saying what everyone thinks but is too scared to say publicly,” one backbencher admitted. “The war on drugs has failed. Time to try something different.”

The commission also recommended expanding drug treatment services, currently facing severe cuts. You can’t arrest your way out of a drug problem,” the report stated. “But you might be able to treat your way out of one.”

Business leaders cautiously welcomed the proposals. “London employers don’t care if someone smoked cannabis at university,” said Tech London Advocates CEO Russ Shaw. “They care about skills. Criminal records for minor drug offences hurt our talent pipeline.”

Even some police officers broke ranks to support reform. One serving detective told the commission anonymously: “I’ve been arresting people for cannabis for 15 years. Complete waste of time. Never stopped anyone using, just gave them a criminal record.”

The report revealed that cannabis prosecutions in London vary wildly by borough, with some areas effectively already operating informal decriminalisation while others pursue aggressive enforcement.

“It’s a postcode lottery,” Lord Falconer said. “Whether you get a criminal record depends more on where you’re caught than what you’ve done. That’s not justice.”

Parent groups expressed mixed views. Sarah Williams, whose son was arrested for possession at 17, said: “That arrest nearly destroyed his future. For what? Something half the Cabinet probably did at university?”

But Margaret Thomson from Families Against Drugs warned: “This sends completely the wrong message to young people. Cannabis isn’t harmless – it can trigger mental health problems and lead to harder drugs.

The commission acknowledged these concerns but argued criminalisation made problems worse. Regulation allows quality control, age restrictions, and health interventions. Prohibition achieves none of these,” the report stated.

As Westminster digests Khan’s intervention, the battle lines are drawn. Reform advocates see momentum building; traditionalists warn of societal breakdown. But with public opinion shifting and evidence mounting, the question may not be whether Britain decriminalises cannabis, but when.

“Change is coming,” Khan predicted. “The only question is whether politicians have the courage to lead it or will be dragged along behind public opinion.”

For now, thousands of young Londoners continue to risk criminal records for something their mayor just said “cannot be justified.” How long that contradiction can persist remains to be seen.