The gloves are off. Former Prime Minister Tony Blair has launched a stinging rebuke of Keir Starmer’s Net Zero strategy, branding it “doomed to fail” and warning that Labour’s current green agenda, led by Ed Miliband, is veering into ideological zealotry. At a time when Starmer’s government is trying to present a united front on climate change, Blair’s public intervention has exposed deep cracks within the party—and raised serious questions about whether Labour can realistically deliver its ambitious environmental goals.

This isn’t just a disagreement over policy; it’s a clash of ideologies, of pragmatism versus idealism. Blair, once hailed as a master of political messaging and electoral strategy, is voicing what many moderates in the party are whispering behind closed doors: that the pursuit of Net Zero, at all costs and speed, could backfire economically and politically.

Starmer now finds himself walking a political tightrope—balancing the demands of a younger, climate-conscious electorate with the economic realities of a country still recovering from inflation, energy shocks, and post-Brexit turbulence.

Background: Labour’s Net Zero Commitments

Labour’s commitment to achieving Net Zero carbon emissions by 2050—or even earlier—is one of its flagship policies. The party has positioned itself as the climate-conscious alternative to the Conservatives, who have been accused of dragging their feet on green issues. The plan includes major investments in renewable energy, transitioning away from fossil fuels, and creating hundreds of thousands of green jobs.

Under Ed Miliband’s leadership as Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change, Labour has pledged to nationalize key energy infrastructures, ban new oil and gas licenses, and push for a green industrial revolution. Miliband has argued that these bold measures are necessary not only for environmental protection but also to drive long-term economic resilience.

However, critics within and outside the party question whether these commitments are grounded in economic realism. Concerns range from the feasibility of infrastructure upgrades to the cost burden on taxpayers and businesses. And this is where Blair’s critique hits hardest—at the intersection of ambition and deliverability.

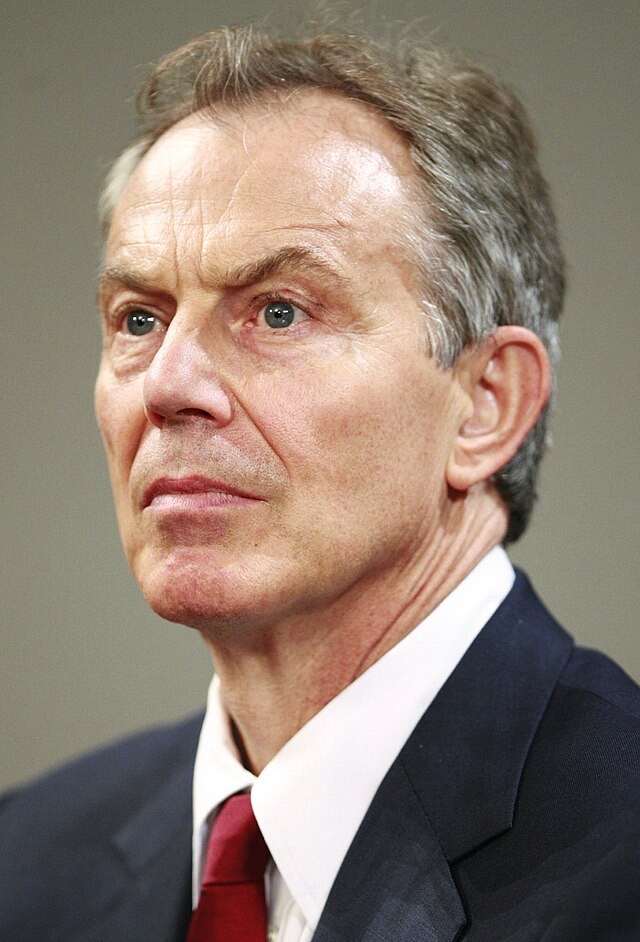

Tony Blair’s Public Rebuke

Blair’s intervention was as dramatic as it was strategic. Speaking at a policy forum, he warned that Labour’s climate policies are veering into territory that could alienate working-class voters and hurt the party’s electoral chances. “We need to be realistic about what can be achieved, and how fast,” Blair said. “To promise the impossible is to guarantee failure.”

He criticized what he sees as an over-reliance on idealistic projections rather than hard-headed analysis, warning that unchecked climate zeal could become Labour’s Achilles heel. While Blair has long supported climate action, he emphasized the need for a pragmatic path—one that doesn’t risk the UK’s economic stability or political cohesion.

His words sent ripples through Westminster. Blair, still influential among centrist Labour MPs and party strategists, essentially gave voice to the growing unease among those who feel the current leadership is overreaching on green policy without a clear, costed roadmap.

Starmer’s Vision vs. Blair’s Realism

Keir Starmer has staked much of his premiership on transformative change, and climate policy is central to that vision. His administration argues that the transition to a green economy isn’t just a moral imperative—it’s an economic opportunity. Investing in solar, wind, and hydrogen, according to Starmer, will reindustrialize the north, retrain workers, and put Britain at the forefront of global climate leadership.

But this vision clashes with Blair’s more incrementalist approach. Blair fears that by promising too much too quickly, Labour risks overpromising and underdelivering—especially when financial constraints are so pressing. In short, Blair is urging caution, realism, and prioritization.

The tension between Starmer’s “New Green Deal” and Blair’s strategic caution reflects a broader ideological divide in Labour: should the party lead the world in climate reform, even at significant short-term economic cost? Or should it temper its goals to ensure long-term political survival?

Ed Miliband and the Charge of ‘Eco-Zealotry’

At the heart of the storm is Ed Miliband. Often a polarizing figure, Miliband has long been one of the most vocal proponents of urgent climate action within Labour. His critics label him an “eco-zealot,” arguing that his policies are driven more by ideology than practicality.

Supporters, however, view him as a visionary—a politician finally matching words with action on the climate crisis. Miliband has proposed sweeping reforms, including a Green New Deal, and has been instrumental in pushing the party to adopt more ambitious targets.

But even some within his own ranks worry that his approach lacks nuance. The proposed speed of the fossil fuel phase-out, for example, has raised alarms in traditional Labour heartlands where jobs in energy, transport, and manufacturing are on the line. The rhetoric of transformation, they argue, must be balanced with transitional support and economic feasibility.

Miliband’s position now seems precarious. With Blair’s broadside casting a shadow over Labour’s climate platform, questions are mounting about whether Starmer can—or should—keep him in such a pivotal role.